Radians are another way of measuring angles, and the measure of an angle can be converted between degrees and radians.

Explain the definition of radians in terms of arc length of a unit circle and use this to convert between degrees and radians

Recall that dividing a circle into 360 parts creates the degree measurement. This is an arbitrary measurement, and we may choose other ways to divide a circle. To find another unit, think of the process of drawing a circle. Imagine that you stop before the circle is completed. The portion that you drew is referred to as an arc. An arc may be a portion of a full circle, a full circle, or more than a full circle, represented by more than one full rotation. The length of the arc around an entire circle is called the circumference of that circle. The circumference of a circle is [latex-display]C = 2 \pi r[/latex-display] If we divide both sides of this equation by [latex]r[/latex], we create the ratio of the circumference, which is always [latex]2\pi[/latex] to the radius, regardless of the length of the radius. So the circumference of any circle is [latex]2\pi \approx 6.28[/latex] times the length of the radius. That means that if we took a string as long as the radius and used it to measure consecutive lengths around the circumference, there would be room for six full string-lengths and a little more than a quarter of a seventh, as shown in the diagram below.

The circumference of a circle compared to the radius: The circumference of a circle is a little more than 6 times the length of the radius.

This brings us to our new angle measure. The radian is the standard unit used to measure angles in mathematics. One radian is the measure of a central angle of a circle that intercepts an arc equal in length to the radius of that circle.

One radian: The angle [latex]t[/latex] sweeps out a measure of one radian. Note that the length of the intercepted arc is the same as the length of the radius of the circle.

Because the total circumference of a circle equals [latex]2\pi[/latex] times the radius, a full circular rotation is [latex]2\pi[/latex] radians.

Radians in a circle: An arc of a circle with the same length as the radius of that circle corresponds to an angle of 1 radian. A full circle corresponds to an angle of [latex]2\pi[/latex] radians; this means that[latex]2\pi[/latex] radians is the same as [latex]360^\circ[/latex].

Note that when an angle is described without a specific unit, it refers to radian measure. For example, an angle measure of 3 indicates 3 radians. In fact, radian measure is dimensionless, since it is the quotient of a length (circumference) divided by a length (radius), and the length units cancel. You may sometimes see radians represented by the symbol [latex]\text[/latex].

Since we now know that the full range of a circle can be represented by either 360 degrees or [latex]2\pi[/latex] radians, we can conclude the following: [latex]\displaystyle < \begin

Convert an angle measuring [latex]\displaystyle< \frac<\pi> >[/latex] radians to degrees. Substitute the angle in radians into the above formula: [latex]\displaystyle < \begin\text &= \text \cdot \frac <\pi>\\ \text &= \frac<\pi> \cdot \frac <\pi>\\ &=\frac> \\ &= 20^ \end >[/latex] Thus we have [latex]\displaystyle< \frac<\pi> \text < radians>= 20^ >[/latex].

An arc length [latex]s[/latex] is the length of the curve along the arc. Just as the full circumference of a circle always has a constant ratio to the radius, the arc length produced by any given angle also has a constant relation to the radius, regardless of the length of the radius. This ratio, called the radian measure, is the same regardless of the radius of the circle—it depends only on the angle. This property allows us to define a measure of any angle as the ratio of the arc length [latex]s[/latex] to the radius [latex]r[/latex]. [latex]\displaystyle < \begin

Measuring radians: (a) In an angle of 1 radian; the arc lengths equals the radius [latex]r[/latex]. (b) An angle of 2 radians has an arc length [latex]s=2r[/latex]. (c) A full revolution is [latex]2\pi[/latex], or about 6.28 radians.

What is the measure of a given angle in radians if its arc length is [latex]4 \pi[/latex], and the radius has length [latex][/latex]12? Substitute the values [latex]s = 4\pi[/latex] and [latex]r = 12[/latex] into the angle formula: [latex]\displaystyle < \begin

We have already defined the trigonometric functions in terms of right triangles. In this section, we will redefine them in terms of the unit circle. Recall that a unit circle is a circle centered at the origin with radius 1. The angle [latex]t[/latex] (in radians ) forms an arc of length [latex]s[/latex]. The x- and y-axes divide the coordinate plane (and the unit circle, since it is centered at the origin) into four quarters called quadrants. We label these quadrants to mimic the direction a positive angle would sweep. The four quadrants are labeled I, II, III, and IV. For any angle [latex]t[/latex], we can label the intersection of its side and the unit circle by its coordinates, [latex](x, y)[/latex]. The coordinates [latex]x[/latex] and [latex]y[/latex] will be the outputs of the trigonometric functions [latex]f(t) = \cos t[/latex] and [latex]f(t) = \sin t[/latex], respectively. This means: [latex]\displaystyle < \beginx &= \cos t \\ y &= \sin t \end >[/latex] The diagram of the unit circle illustrates these coordinates.

Unit circle: Coordinates of a point on a unit circle where the central angle is [latex]t[/latex] radians.

Note that the values of [latex]x[/latex] and [latex]y[/latex] are given by the lengths of the two triangle legs that are colored red. This is a right triangle, and you can see how the lengths of these two sides (and the values of [latex]x[/latex] and [latex]y[/latex]) are given by trigonometric functions of [latex]t[/latex].

For an example of how this applies, consider the diagram showing the point with coordinates [latex]\displaystyle<\left(-\frac, \frac\right) >[/latex] on a unit circle.

Point on a unit circle: The point [latex]\displaystyle< \left(-\frac, \frac\right) >[/latex] on a unit circle.We know that, for any point on a unit circle, the [latex]x[/latex]-coordinate is [latex]\cos t[/latex] and the [latex]y[/latex]-coordinate is [latex]\sin t[/latex]. Applying this, we can identify that [latex]\displaystyle>[/latex] and [latex]\displaystyle>[/latex] for the angle [latex]t[/latex] in the diagram.

Recall that [latex]\displaystyle>[/latex]. Applying this formula, we can find the tangent of any angle identified by a unit circle as well. For the angle [latex]t[/latex] identified in the diagram of the unit circle showing the point [latex]\displaystyle<\left(-\frac, \frac\right)>[/latex], the tangent is: [latex-display]\displaystyle\tan t &= \frac \\&= \frac<-\frac><-\frac> \\&= 1\end>[/latex-display] We have previously discussed trigonometric functions as they apply to right triangles. This allowed us to make observations about the angles and sides of right triangles, but these observations were limited to angles with measures less than [latex]90^[/latex]. Using the unit circle, we are able to apply trigonometric functions to angles greater than [latex]90^[/latex].

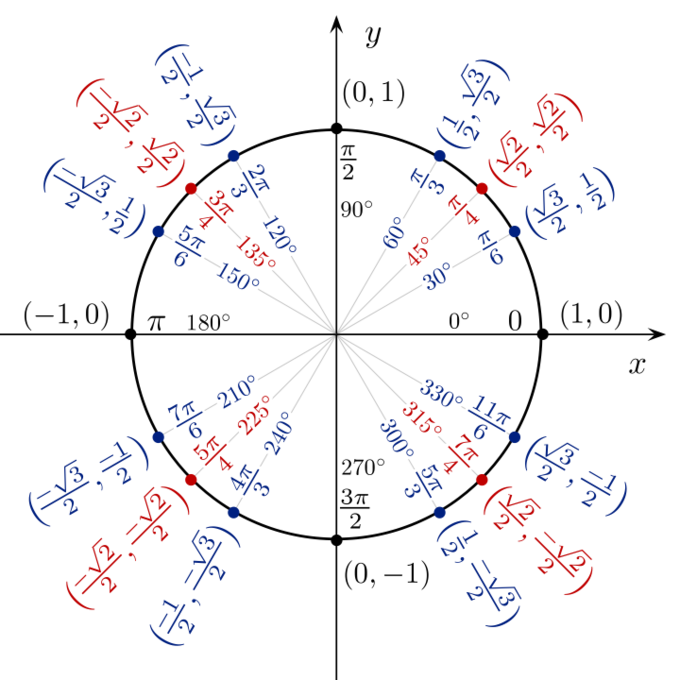

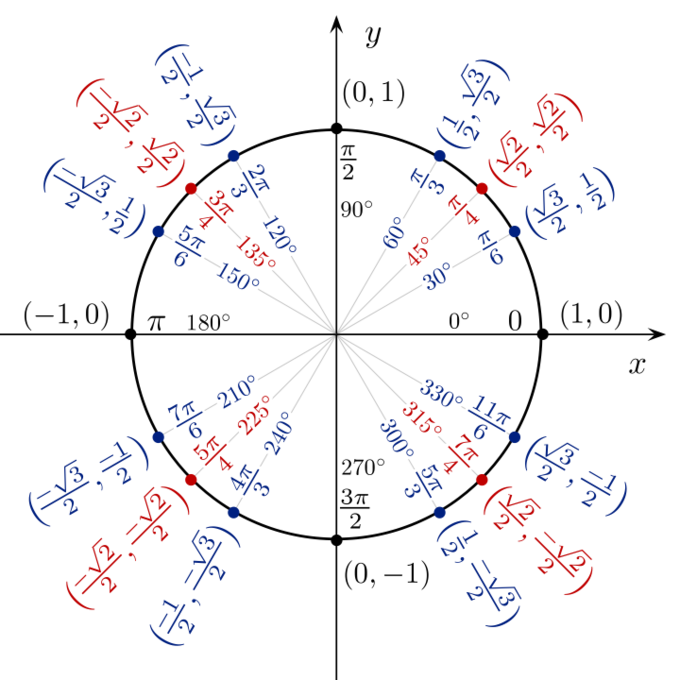

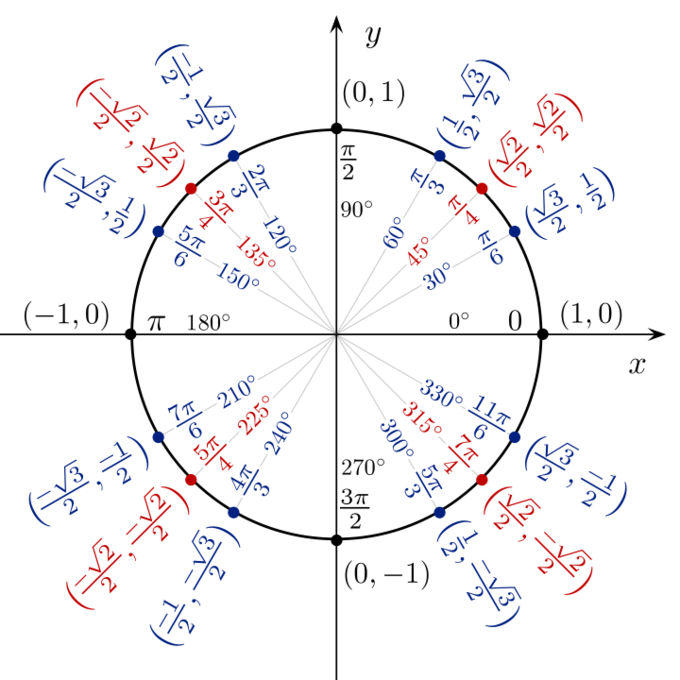

The coordinates of certain points on the unit circle and the the measure of each angle in radians and degrees are shown in the unit circle coordinates diagram. This diagram allows one to make observations about each of these angles using trigonometric functions.

Unit circle coordinates: The unit circle, showing coordinates and angle measures of certain points.

We can find the coordinates of any point on the unit circle. Given any angle [latex]t[/latex], we can find the [latex]x[/latex]- or [latex]y[/latex]-coordinate at that point using [latex]x = \text t[/latex] and [latex]y = \text t[/latex]. The unit circle demonstrates the periodicity of trigonometric functions. Periodicity refers to the way trigonometric functions result in a repeated set of values at regular intervals. Take a look at the [latex]x[/latex]-values of the coordinates in the unit circle above for values of [latex]t[/latex] from [latex]0[/latex] to [latex]2<\pi>[/latex]: [latex-display]>, \frac<\sqrt>, \frac, 0, -\frac, -\frac<\sqrt>, -\frac>, -1, -\frac>, -\frac<\sqrt>, -\frac, 0, \frac, \frac<\sqrt>, \frac>, 1>[/latex-display] We can identify a pattern in these numbers, which fluctuate between [latex]-1[/latex] and [latex]1[/latex]. Note that this pattern will repeat for higher values of [latex]t[/latex]. Recall that these [latex]x[/latex]-values correspond to [latex]\cos t[/latex]. This is an indication of the periodicity of the cosine function.

Solve [latex]\displaystyle< \sin< \left(\frac<7\pi>\right) > >[/latex]. It seems like this would be complicated to work out. However, notice that the unit circle diagram shows the coordinates at [latex]\displaystyle< t = \frac<7\pi> >[/latex]. Since the [latex]y[/latex]-coordinate corresponds to [latex]\sin t[/latex], we can identify that [latex-display]\displaystyle\right)> = -\frac >[/latex-display]

The unit circle and a set of rules can be used to recall the values of trigonometric functions of special angles.

Explain how the properties of sine, cosine, and tangent and their signs in each quadrant give their values for each of the special angles

Recall that certain angles and their coordinates, which correspond to [latex]x = \cos t[/latex] and [latex]y = \sin t[/latex] for a given angle [latex]t[/latex], can be identified on the unit circle.

Unit circle: Special angles and their coordinates are identified on the unit circle.

The angles identified on the unit circle above are called special angles; multiples of [latex]\pi[/latex], [latex]\frac<\pi>[/latex], [latex][/latex][latex]\frac<\pi>[/latex], [latex]\frac<\pi>[/latex], and [latex]\frac<\pi>[/latex] ([latex]180^\circ[/latex][latex][/latex], [latex]90^\circ[/latex], [latex]60^\circ[/latex], [latex]45^\circ[/latex], and [latex]30^\circ[/latex]). These have relatively simple expressions. Such simple expressions generally do not exist for other angles. Some examples of the algebraic expressions for the sines of special angles are:

[latex]\displaystyle < \begin\sin <\left( 0^\right)> &= 0 \\ \sin <\left( 30^\right)> &= \frac \\ \sin <\left( 45^\right)> &= \frac<\sqrt> \\ \sin <\left( 60^\right)> &= \frac> \\ \sin <\left( 90^\right)> &= 1 \\ \end >[/latex] The expressions for the cosine functions of these special angles are also simple. Note that while only sine and cosine are defined directly by the unit circle, tangent can be defined as a quotient involving these two: [latex]\displaystyle< \tan t = \frac >[/latex] Tangent functions also have simple expressions for each of the special angles. We can observe this trend through an example. Let's find the tangent of [latex]60^[/latex]. First, we can identify from the unit circle that: [latex]\displaystyle < \begin\sin< \left(60^\right) > &= \frac> \\ \cos< \left(60^\right) > &= \frac \end >[/latex] We can easily calculate the tangent: [latex]\displaystyle < \begin\tan<\left(60^\right)> &= \frac<\sin<\left(60^\right)>><\cos<\left(60^\right)>> \\ &= \frac<\frac>><\frac> \\ &= \frac> \cdot \frac \\ &= \sqrt \end >[/latex]

An understanding of the unit circle and the ability to quickly solve trigonometric functions for certain angles is very useful in the field of mathematics. Applying rules and shortcuts associated with the unit circle allows you to solve trigonometric functions quickly. The following are some rules to help you quickly solve such problems.

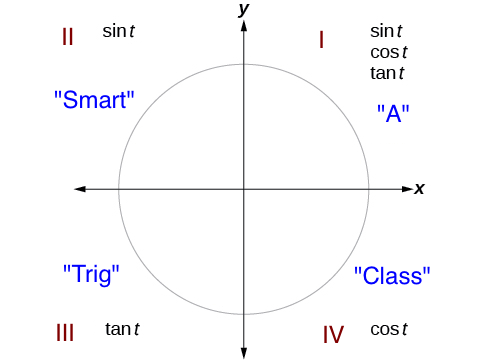

The sign of a trigonometric function depends on the quadrant that the angle falls in. To help remember which of the trigonometric functions are positive in each quadrant, we can use the mnemonic phrase “A Smart Trig Class.” Each of the four words in the phrase corresponds to one of the four quadrants, starting with quadrant I and rotating counterclockwise. In quadrant I, which is “A,” all of the trigonometric functions are positive. In quadrant II, “Smart,” only sine is positive. In quadrant III, “Trig,” only tangent is positive. Finally, in quadrant IV, “Class,” only cosine is positive.

Sign rules for trigonometric functions: The trigonometric functions are each listed in the quadrants in which they are positive.

Take a close look at the unit circle, and note that [latex]\sin t[/latex] and [latex]\cos t[/latex] take certain values as they fluctuate between [latex]-1[/latex] and [latex]1[/latex]. You will notice that they take on the value of zero, as well as the positive and negative values of three particular numbers: [latex]\displaystyle>>[/latex], [latex]\displaystyle<\frac<\sqrt>>[/latex], and [latex]\displaystyle>[/latex]. Identifying reference angles will help us identify a pattern in these values. Reference angles in quadrant I are used to identify which value any angle in quadrants II, III, or IV will take. This means that we only need to memorize the sine and cosine of three angles in quadrant I: [latex]30^[/latex], [latex]45^[/latex], and [latex]60^[/latex]. For any given angle in the first quadrant, there is an angle in the second quadrant with the same sine value. Because the sine value is the [latex]y[/latex]-coordinate on the unit circle, the other angle with the same sine will share the same [latex]y[/latex]-value, but have the opposite [latex]x[/latex]-value. Therefore, its cosine value will be the opposite of the first angle’s cosine value. Likewise, there will be an angle in the fourth quadrant with the same cosine as the original angle. The angle with the same cosine will share the same [latex]x[/latex]-value but will have the opposite [latex]y[/latex]-value. Therefore, its sine value will be the opposite of the original angle’s sine value. As shown in the diagrams below, angle [latex]\alpha[/latex] has the same sine value as angle [latex]t[/latex]; the cosine values are opposites. Angle [latex]\beta[/latex] has the same cosine value as angle [latex]t[/latex]; the sine values are opposites. [latex]\displaystyle < \begin\sin t = \sin \alpha \quad &\text \quad \cos t = -\cos \alpha \\ \sin t = -\sin \beta \quad &\text \quad \cos t = \cos \beta \end >[/latex]

Reference angles: In the left figure, [latex]t[/latex] is the reference angle for [latex]\alpha[/latex]. In the right figure, [latex]t[/latex] is the reference angle for [latex]\beta[/latex].

Recall that an angle’s reference angle is the acute angle, [latex]t[/latex], formed by the terminal side of the angle [latex]t[/latex] and the horizontal axis. A reference angle is always an angle between [latex]0[/latex] and [latex]90^[/latex], or [latex]0[/latex] and [latex]\displaystyle<\frac<\pi>>[/latex] radians. For any angle in quadrants II, III, or IV, there is a reference angle in quadrant I.

Reference angles in each quadrant: For any angle in quadrants II, III, or IV, there is a reference angle in quadrant I.

Thus, in order to recall any sine or cosine of a special angle, you need to be able to identify its angle with the [latex]x[/latex]-axis in order to compare it to a reference angle. You will then identify and apply the appropriate sign for that trigonometric function in that quadrant.

Find [latex]\tan (225^)[/latex], applying the rules above. First, note that [latex]225^[/latex] falls in the third quadrant:

Angle [latex]225^[/latex] on a unit circle: The angle [latex]225^[/latex]falls in quadrant III.Subtract [latex]225^[/latex] from [latex]180^[/latex] to identify the reference angle:

[latex]\displaystyle < \begin\left| 180^ - 225^ \right| &= \left|-45^ \right| \\ &= 45^ \end >[/latex] In other words, [latex]225^[/latex] falls [latex]45^[/latex] from the [latex]x[/latex]-axis. The reference angle is [latex]45^[/latex]. Recall that [latex]\displaystyle<\sin< \left(45^\right)> = \frac> >[/latex] However, the rules described above tell us that the sine of an angle in the third quadrant is negative. So we have [latex]\displaystyle<\sin< \left(225^\right)> = -\frac> >[/latex] Following the same process for cosine, we can identify that [latex-display]\displaystyle< \cos< \left(225^\right)> = -\frac> >[/latex-display] We can find [latex]\tan (225^)[/latex] by dividing [latex]\sin (225^)[/latex] by [latex]\cos (225^)[/latex]: [latex]\displaystyle < \begin\tan< \left(225^\right)> &= \frac<\sin(225^)><\cos (225^)> \\ &= \frac<-\frac>><-\frac>> \\ &= -\frac> \cdot -\frac> \\ &= 1 \end >[/latex]

The functions sine and cosine can be graphed using values from the unit circle, and certain characteristics can be observed in both graphs.

Recall that the sine and cosine functions relate real number values to the [latex]x[/latex]- and [latex]y[/latex]-coordinates of a point on the unit circle. So what do they look like on a graph on a coordinate plane? Let’s start with the sine function, [latex]y = \sin x[/latex]. We can create a table of values and use them to sketch a graph. Below are some of the values for the sine function on a unit circle, with the [latex]x[/latex]-coordinate being the angle in radians and the [latex]y[/latex]-coordinate being [latex]\sin x[/latex]: [latex]\displaystyle< (0, 0) \quad (\frac<\pi>, \frac) \quad (\frac<\pi>, \frac<\sqrt>) \quad (\frac<\pi>, \frac<\sqrt>) \quad (\frac<\pi>, 1) \\ (\frac<2\pi>, \frac<\sqrt>) \quad (\frac<3\pi>, \frac<\sqrt>) \quad (\frac<5\pi>, \frac) \quad (\pi, 0) >[/latex] Plotting the points from the table and continuing along the [latex]x[/latex]-axis gives the shape of the sine function.

Graph of the sine function: Graph of points with [latex]x[/latex] coordinates being angles in radians, and [latex]y[/latex] coordinates being the function [latex]\sin x[/latex].

Notice how the sine values are positive between [latex]0[/latex] and [latex]\pi[/latex], which correspond to the values of the sine function in quadrants I and II on the unit circle, and the sine values are negative between [latex]\pi[/latex] and [latex]2\pi[/latex], which correspond to the values of the sine function in quadrants III and IV on the unit circle.

Plotting values of the sine function: The points on the curve [latex]y = \sin x[/latex] correspond to the values of the sine function on the unit circle.

Now let’s take a similar look at the cosine function, [latex]f(x) = \sin x[/latex]. Again, we can create a table of values and use them to sketch a graph. Below are some of the values for the sine function on a unit circle, with the [latex]x[/latex]-coordinate being the angle in radians and the [latex]y[/latex]-coordinate being [latex]\cos x[/latex]:

[latex]\displaystyle< (0, 1) \quad (\frac<\pi>, \frac>) \quad (\frac<\pi>, \frac<\sqrt>) \quad (\frac<\pi>, \frac) \quad (\frac<\pi>, 0) \\ (\frac<2\pi>, -\frac) \quad (\frac<3\pi>, -\frac<\sqrt>) \quad (\frac<5\pi>, -\frac>) \quad (\pi, -1) >[/latex] As with the sine function, we can plots points to create a graph of the cosine function.

Graph of the cosine function: The points on the curve [latex]y = \cos x[/latex] correspond to the values of the cosine function on the unit circle.

Because we can evaluate the sine and cosine of any real number, both of these functions are defined for all real numbers. By thinking of the sine and cosine values as coordinates of points on a unit circle, it becomes clear that the range of both functions must be the interval [latex]\left[-1, 1 \right][/latex].

In the graphs for both sine and cosine functions, the shape of the graph repeats after [latex]2\pi[/latex], which means the functions are periodic with a period of [latex]2\pi[/latex]. A periodic function is a function with a repeated set of values at regular intervals. Specifically, it is a function for which a specific horizontal shift, [latex]P[/latex], results in a function equal to the original function: [latex-display]f(x + P) = f(x)[/latex-display] for all values of [latex]x[/latex] in the domain of [latex]f[/latex]. When this occurs, we call the smallest such horizontal shift with [latex]P>0[/latex] the period of the function. The diagram below shows several periods of the sine and cosine functions.

Periods of the sine and cosine functions: The sine and cosine functions are periodic, meaning that a specific horizontal shift, [latex]P[/latex], results in a function equal to the original function:[latex]f(x + P) = f(x)[/latex].

Looking again at the sine and cosine functions on a domain centered at the [latex]y[/latex]-axis helps reveal symmetries. As we can see in the graph of the sine function, it is symmetric about the origin, which indicates that it is an odd function. All along the graph, any two points with opposite [latex]x[/latex] values also have opposite [latex]y[/latex] values. This is characteristic of an odd function: two inputs that are opposites have outputs that are also opposites. In other words, if [latex]\sin (-x) = - \sin x[/latex].

Odd symmetry of the sine function: The sine function is odd, meaning it is symmetric about the origin.

The graph of the cosine function shows that it is symmetric about the y-axis. This indicates that it is an even function. For even functions, any two points with opposite [latex]x[/latex]-values have the same function value. In other words, [latex]\cos (-x) = \cos x[/latex]. We can see from the graph that this is true by comparing the [latex]y[/latex]-values of the graph at any opposite values of [latex]x[/latex].

Even symmetry of the cosine function: The cosine function is even, meaning it is symmetric about the [latex]y[/latex]-axis.

The tangent function can be graphed by plotting [latex]\left(x,f(x)\right)[/latex] points. The shape of the function can be created by finding the values of the tangent at special angles. However, it is not possible to find the tangent functions for these special angles with the unit circle. We apply the formula, [latex]\displaystyle< \tan x = \frac >[/latex] to determine the tangent for each value. We can analyze the graphical behavior of the tangent function by looking at values for some of the special angles. Consider the points below, for which the [latex]x[/latex]-coordinates are angles in radians, and the [latex]y[/latex]-coordinates are [latex]\tan x[/latex]: [latex]\displaystyle< (-\frac<\pi>, \text) \quad (-\frac<\pi>, -\sqrt) \quad (-\frac<\pi>, -1) \quad (-\frac<\pi>, -\frac<\sqrt>) \quad (0, 0) \\ (\frac<\pi>, \frac<\sqrt>) \quad (\frac<\pi>, 1) \quad (\frac<\pi>, \sqrt) \quad (\frac<\pi>, \text) >[/latex] Notice that [latex]\tan x[/latex] is undefined at [latex]\displaystyle>[/latex] and [latex]\displaystyle>[/latex]. The above points will help us draw our graph, but we need to determine how the graph behaves where it is undefined. Let's consider the last four points. We can identify that the values of [latex]y[/latex] are increasing as [latex]x[/latex] increases and approaches [latex]\displaystyle<\frac<\pi>>[/latex]. We could consider additional points between [latex]\displaystyle[/latex] and [latex]\displaystyle>[/latex], and we would see that this holds. Likewise, we can see that [latex]y[/latex] decreases as [latex]x[/latex] approaches [latex]\displaystyle<-\frac<\pi>>[/latex], because the outputs get smaller and smaller. Recall that there are multiple values of [latex]x[/latex] that can give [latex]\cos x = 0[/latex]. At any such point, [latex]\tan x[/latex] is undefined because [latex]\displaystyle<\tan x = \frac>[/latex]. At values where the tangent function is undefined, there are discontinuities in its graph. At these values, the graph of the tangent has vertical asymptotes.

Graph of the tangent function: The tangent function has vertical asymptotes at [latex]\displaystyle

As with the sine and cosine functions, tangent is a periodic function. This means that its values repeat at regular intervals. The period of the tangent function is [latex]\pi[/latex] because the graph repeats itself on [latex]x[/latex]-axis intervals of [latex]k\pi[/latex], where [latex]k[/latex] is a constant. In the graph of the tangent function on the interval [latex]\displaystyle<-\frac<\pi>>[/latex] to [latex]\displaystyle<\frac<\pi>>[/latex], we can see the behavior of the graph over one complete cycle of the function. If we look at any larger interval, we will see that the characteristics of the graph repeat. The graph of the tangent function is symmetric around the origin, and thus is an odd function. In other words, [latex]\text(-x) = - \text x[/latex] for any value of [latex]x[/latex]. Any two points with opposite values of [latex]x[/latex] produce opposite values of [latex]y[/latex]. We can see that this is true by considering the [latex]y[/latex] values of the graph at any opposite values of [latex]x[/latex]. Consider [latex]\displaystyle

Calculate values for the trigonometric functions that are the reciprocals of sine, cosine, and tangent

We have discussed three trigonometric functions: sine, cosine, and tangent. Each of these functions has a reciprocal function, which is defined by the reciprocal of the ratio for the original trigonometric function. Note that reciprocal functions differ from inverse functions. Inverse functions are a way of working backwards, or determining an angle given a trigonometric ratio; they involve working with the same ratios as the original function. The three reciprocal functions are described below.

The secant function is the reciprocal of the cosine function, and is abbreviated as [latex]\sec[/latex]. It can be described as the ratio of the length of the hypotenuse to the length of the adjacent side in a triangle. [latex]\displaystyle < \begin

The cosecant function is the reciprocal of the sine function, and is abbreviated as[latex]\csc[/latex]. It can be described as the ratio of the length of the hypotenuse to the length of the opposite side in a triangle. [latex]\displaystyle < \begin

The cotangent function is the reciprocal of the tangent function, and is abbreviated as [latex]\cot[/latex]. It can be described as the ratio of the length of the adjacent side to the length of the hypotenuse in a triangle. [latex]\displaystyle < \begin

We now recognize six trigonometric functions that can be calculated using values in the unit circle. Recall that we used values for the sine and cosine functions to calculate the tangent function. We will follow a similar process for the reciprocal functions, referencing the values in the unit circle for our calculations. For example, let's find the value of [latex]\sec<\left(\frac<\pi>\right)>[/latex]. Applying [latex]\displaystyle>[/latex], we can rewrite this as: [latex]\displaystyle< \sec<\left(\frac<\pi>\right)>= \frac<\cos<\left(<\frac<\pi>>\right)>> >[/latex] From the unit circle, we know that [latex]\displaystyle<\cos<\left(<\frac<\pi>>\right)>= \frac>[/latex]. Using this, the value of [latex]\displaystyle< \sec<\left(\frac<\pi>\right)>>[/latex] can be found: [latex]\displaystyle < \begin\sec<\left(\frac<\pi>\right)> &= \frac<\frac> \\ &= 2 \end >[/latex] The other reciprocal functions can be solved in a similar manner.

Use the unit circle to calculate [latex]\sec t[/latex], [latex]\cot t[/latex], and [latex]\csc t[/latex] at the point [latex]\displaystyle<\left(-\frac<\sqrt<3>>, \frac\right)>[/latex].

Point on a unit circle: The point [latex]\displaystyle<\left(-\frac<\sqrt<3>>, \frac\right)>[/latex], shown on a unit circle.

Because we know the [latex](x, y)[/latex] coordinates of the point on the unit circle indicated by angle [latex]t[/latex], we can use those coordinates to find the three functions.

Recall that the [latex]x[/latex]-coordinate gives the value for the cosine function, and the [latex]y[/latex]-coordinate gives the value for the sine function. In other words: [latex]\displaystyle < \beginx &= \cos t \\ &= -\frac> \end >[/latex] and [latex]\displaystyle < \beginy &= \sin t \\ &= \frac \end >[/latex] Using this information, the values for the reciprocal functions at angle [latex]t[/latex] can be calculated: [latex]\displaystyle < \begin\sec t &= \frac \\ &= \frac \\ &= \left(\frac<-\frac>> \right)\\ &= -\frac> \\ &= \left(-\frac> \cdot \frac>> \right)\\ &= -\frac> \end >[/latex] [latex]\displaystyle < \begin\cot t &= \frac \\ &= \frac \\ &= \left(\frac<-\frac>><\frac>\right) \\ &= \left(-\frac>\cdot \frac \right) \\ &= -\sqrt \end >[/latex] [latex]\displaystyle < \begin\csc t &= \frac \\ & = \frac \\ & = \left(\frac<\frac>\right) \\ & = 2 \end >[/latex]

Describe the characteristics of the graphs of the inverse trigonometric functions, noting their domain and range restrictions

Inverse trigonometric functions are used to find angles of a triangle if we are given the lengths of the sides. Inverse trigonometric functions can be used to determine what angle would yield a specific sine, cosine, or tangent value. To use inverse trigonometric functions, we need to understand that an inverse trigonometric function “undoes” what the original trigonometric function “does,” as is the case with any other function and its inverse. The inverse of sine is arcsine (denoted [latex]\arcsin[/latex]), the inverse of cosine is arccosine (denoted [latex]\arccos[/latex]), and the inverse of tangent is arctangent (denoted [latex]\arctan[/latex]). Note that the domain of the inverse function is the range of the original function, and vice versa. An exponent of [latex]-1[/latex] is used to indicate an inverse function. For example, if [latex]f(x) = \sin x[/latex],then we would write [latex]f^<-1>(x) = \sin^ <-1>x[/latex]. Be aware that [latex]\sin^ <-1>x[/latex] does not mean [latex]\displaystyle>[/latex]. The reciprocal function is [latex]\displaystyle>[/latex], which is not the same as the inverse function. For a one-to-one function, if [latex]f(a) = b[/latex], then an inverse function would satisfy [latex]f^<-1>(b) = a[/latex]. However, the sine, cosine, and tangent functions are not one-to-one functions. The graph of each function would fail the horizontal line test. In fact, no periodic function can be one-to-one because each output in its range corresponds to at least one input in every period, and there are an infinite number of periods. As with other functions that are not one-to-one, we will need to restrict the domain of each function to yield a new function that is one-to-one. We choose a domain for each function that includes the number [latex]0[/latex].

Sine and cosine functions within restricted domains: (a) The sine function shown on a restricted domain of [latex]\left[-\frac<\pi>, \frac<\pi>\right][/latex]; (b) The cosine function shown on a restricted domain of [latex]\left[0, \pi\right][/latex].

The graph of the sine function is limited to a domain of [latex][-\frac<\pi>, \frac<\pi>][/latex], and the graph of the cosine function limited is to [latex][0, \pi][/latex]. The graph of the tangent function is limited to [latex]\left(-\frac<\pi>, \frac<\pi>\right)[/latex].

The tangent function shown on a restricted domain of [latex]\left(-\frac<\pi>, \frac<\pi>\right)[/latex]. These choices for the restricted domains are somewhat arbitrary, but they have important, helpful characteristics. Each domain includes the origin and some positive values, and most importantly, each results in a one-to-one function that is invertible. The conventional choice for the restricted domain of the tangent function also has the useful property that it extends from one vertical asymptote to the next, instead of being divided into pieces by an asymptote.

We can define the inverse trigonometric functions as follows. Note the domain and range of each function. The inverse sine function [latex]y = \sin^<-1>x [/latex] means [latex]x = \sin y[/latex]. The inverse sine function can also be written [latex]\arcsin x[/latex]. [latex-display]\displaystylex \quad \text \quad \left[-1, 1\right] \quad \text \quad \left[-\frac<\pi>, \frac<\pi>\right]>[/latex-display] The inverse cosine function [latex]y = \cos^<-1>x [/latex] means [latex]x = \cos y[/latex]. The inverse cosine function can also be written [latex]\arccos x[/latex]. [latex-display]\displaystylex \quad \text \quad \left[-1, 1\right] \quad \text \quad \left[0, \pi\right]>[/latex-display] The inverse tangent function [latex]y = \tan^<-1>x[/latex] means [latex]x = \tan y[/latex]. The inverse tangent function can also be written [latex]\arctan x[/latex]. [latex-display]\displaystylex \quad \text \quad \left(-\infty, \infty\right) \quad \text \quad \left(-\frac<\pi>, \frac<\pi>\right)>[/latex-display]

The sine function and inverse sine (or arcsine) function: The arcsine function is a reflection of the sine function about the line [latex]y = x[/latex].

To find the domain and range of inverse trigonometric functions, we switch the domain and range of the original functions.

The cosine function and inverse cosine (or arccosine) function: The arccosine function is a reflection of the cosine function about the line [latex]y = x[/latex].

Each graph of the inverse trigonometric function is a reflection of the graph of the original function about the line [latex]y = x[/latex].

The tangent function and inverse tangent (or arctangent) function: The arctangent function is a reflection of the tangent function about the line [latex]y = x[/latex].